The Thing (1982)

- nickkarner

- Jan 1, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 15, 2024

“It’s not the dog we need.” Well, Constable Butterman, with all due respect to a fellow Point Break enthusiast, I respectfully disagree. We very much do need the dog or else John Carpenter’s masterpiece of distrust and paranoia wouldn’t be half as effective. Of course, my memory is a bit hazy, so I’m choosing to remember Hot Fuzz as over two hours of Simon Pegg and Nick Frost talking about The Thing (1982) instead of engaging in wacky antics involving septuagenarian’s and “the greater good.” There have been many great canine performances: Cujo, the shepherd in White Dog, Annie in I am Legend, Milo in The Mask, Toto in Wizard of Oz, that bitch diva Lassie, and maybe the greatest of all, Zowie, the rocking chair dog from Pet Sematary II. Not to be confused with Poochie, the rockin’ dog, who died on the way back to his home planet. All fine four-legged performers, but there’s one pup who stands out among the rest.

If only those scientists at the Antarctic research center U.S. Outpost 31 hadn’t been so busy playing pool, getting high, and watching old episodes of “Let’s Make a Deal,” maybe they’d’ve found the time to learn some damn Norwegian. While a big fuzzball of a Husky gallops through the snow (happily, I imagine, considering how much my own idiot dog loves it), a couple of ticked-off Nordic gentlemen desperately try to bomb and shoot it from their chopper. The super-friendly pup zeroes in on Clark (Richard Masur, It), a dog person if there ever was one. I kept asking myself: Since Richard Masur doesn’t make it out of this movie alive, who’s going to teach Corey Haim to drive? Anyways, those Norwegians pretty much explain everything “Beautiful language, eh, Marge?” but us dumbass Americans can’t be bothered to decipher some jibber jabber about a re-animated alien monster who can perfectly replicate any creature it comes in contact with. A pesky case of butterfingers involving a grenade ensues and those dudes are toast. And so begins a film that, like much of Carpenter’s work, was far ahead of its time and got pounded into oblivion by a funny little Reese's Pieces-munching alien only to rise up and become not only one of the finest remakes of all time, but one of the greatest horror movies as well.

I try to broaden my cinematic horizons as much as possible, so sometimes I forget how enjoyable comfort food movies can be. Re-watching The Thing, it all came flooding back. The grotesque beauty of Rob Bottin’s creature effects. Dean Cundey’s cinematography, which perfectly captures the feeling of cold and isolation. Ennio Morricone’s subtle, unobtrusive score (much of which would be eliminated and later utilized by Tarantino in The Hateful Eight). A pitch-perfect cast of character actors delivering realistic, lived-in performances thanks to Bill Lancaster’s (The Bad News Bears) nihilistic, compelling script. John Carpenter’s steady, controlled direction. Those wonderful behind-the-scenes details: The title shot being made using Glad-style garbage bags, a real amputee having Richard Dysart’s molded face placed upon him for the climactic “chest jaw” scene, Drew Struzan’s amazing poster art, Bottin pretty much having a nervous breakdown working himself to the bone, Kurt Russell’s fake hand during the blood test, and most importantly of all, that dog.

In one of the film’s eeriest shots, the camera tracks the dog as it wanders a hallway and, for a moment, the alien/dog literally appears to pause and consider whom it will attack and replicate. The scene ends with a shot of absolute ambiguity, much like the film’s legendary conclusion, by having the pup peer into someone’s room, with only the occupant’s shadow to give us any clue of their identity. It’s highly impressive and risky as hell asking a dog to essentially shoulder the burden of establishing the ominous mood of your sci-fi/horror film, but he accomplishes his task like a pro.

What’s so striking about the acting in The Thing is the total lack of vanity each performer brings to their role. It’s been argued that, like the desolate, Antarctic-setting, the ensemble isn’t particularly warm and fuzzy and they don’t go through many major, emotional arcs or journeys, thus leading to a conclusion that the story is a rather cold one, no pun intended. My counter-argument is that this is the strength of the film. These are supposed to be ordinary men dropped into a terrifying and extraordinary situation.

Even Kurt Russell, playing the Chess Wizard “cheatin’ bitch” sore loser MacReady, is never asked to deliver a star performance, despite being a genuine movie star at the time. We get just enough subtle character work to get a feel for who these guys are: the roller-skating cook Nauls (T.K. Carter, Runaway Train) motioning to turn down his music that’s keeping Bennings (Peter Maloney, Requiem for a Dream) awake, then skipping it; medical assistant Fuchs (Joel Polis, True Believer) sharing his suspicions with MacReady but not being aggressive enough to save himself or anyone else; Childs (Keith David, They Live) refusing to believe any of this “voodoo bullshit,”; helicopter pilot and stoner Palmer (David Clennon, Missing) watching as Mac takes Dr. Copper (Richard Dysart, L.A. Law, Prophecy) up in the chopper and barely able to conceal his innate jealousy of his counterpart’s skills “He knows what he’s doing.”

Still, due to the darkness and bleak nature of the material, it’s easy to forget about the three most emotional performances. Windows (Thomas G. Waites, The Warriors), the beleaguered radio operator, is the most frantic and paranoid of the group, but a special mention should be made for the station commander Garry, wonderfully played by Donald Moffat (Clear and Present Danger). Besides his crowd-pleasing bit of dialogue after being cleared of any Thing-related mishaps, “I know you gentlemen have been through a lot, but when you find the time, I'd rather not spend the rest of this winter TIED TO THIS FUCKING COUCH!”, he also gets to have one of the few heartbreaking moments of the film, besides the attack on those poor huskies. After Bennings has been exposed as a thing and burned alive in a great scene where he’s almost completely turned save for a long, disfigured hand and a raspy alien roar, Garry is stunned. The look of pain and confusion is genuinely affecting as he says: “MacReady, I know Bennings! I’ve known him for ten years. He’s my friend.” Moffat has been a stern but fair leader up until this point, but his inability to control or understand the situation renders him helpless.

However, the most badass good guy-turned-villain award must go to Dr. Blair, played by the moustache-less Wilford Brimley, here credited as A. Wilford Brimley, as if there’s more than one, but I can assure you, there is not. Ah, the beauty of impossible technology! Brimley is not only a medical scientist with a strong stomach and whose monologues about what the thing is and how it works are dazzling and compelling, but he’s also a goddamn computer genius because he develops a program which breaks down the hypothetical nature of what sort of damage this alien could do to the planet if it escapes. His eventual mental breakdown and subsequent destruction of every viable option the others have to escape or communicate with the outside world is both desperate and inadvertently sinister.

The character of Blair remains the movie’s most fascinating enigma and raises the question of when exactly did Blair get taken over and what precisely are the rules of how the thing works. His reasoning for smashing the radio equipment is sound, although a bit extreme: “If the cell gets out, it could imitate everything on Earth and it’s not gonna stop!” The same goes for the helicopter, but then we discover that he’s somehow used the parts to build his own spaceship, a slightly ridiculous contrivance that’s forgivable. The smartest reveal arrives when MacReady checks in on Blair, who’s been confined, and he’s got a noose hanging by his side. It begs the question: Was he planning on killing himself to avoid being taken over and was stopped by an errant Thing cell?

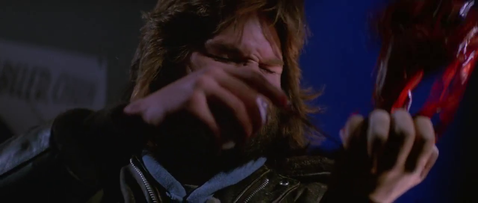

This question also applies to Palmer, whose legendary “You’ve gotta be fuckin’ kidding” comes after Copper’s had his arms bitten off and Norris’ (Charles Hallahan, Body of Evidence, Dante’s Peak) chest bursts wide open in a squirting mass of green and yellow wormlike strands (a happy effects accident, apparently, and one which features a fantastic camera push-in). His head stretches backwards and detaches itself from the torso, revealing long stalks of vegetative-looking tubes. The insanity of the “spider head” sprouting antennae-eyeballs and creepy crawly legs prompts Palmer’s applause-worthy piece of profanity. But later, he turns out to be the thing during the awesome blood test (parodied beautifully on the head lice episode of South Park “Kelly!”) and it’s absolute chaos as Palmer’s head snaps in two and in a bloody frenzy, bites into Windows and flings him around the room. It would be cartoonish if it weren’t so gruesomely over-the-top and true to what the movie is capable of. I have to assume that although the thing doesn’t want any of its replicants to be destroyed, it’s ruthless enough to “hide inside its victim” by pretending to be shocked by the mayhem around it.

So many personal touches and bits of business make the film richer than people give it credit for. The simplicity of the dog staring up at everyone from under the pool table, which we later come to realize is its way of scanning the room and sizing everyone up. The understandable assumption that the Norwegians merely went nuts through cabin fever. There’s a realism to the infamous kennel sequence where Childs, sporting that awesome flame thrower, just stares at the monstrosity before him. It’s a very human moment. The use of cicadas during this scene feels very appropriate and has been copied many times since. I also adore the idea that this thing may be over a hundred thousand years old and the opening in which a UFO blasts through Earth’s atmosphere is fascinating since it makes one imagine at what time period it might’ve landed. The fact that the men can’t communicate with the outside world makes it feel as though they’re the last men on Earth. And hey, maybe they are?

John Carpenter has always been very open about the disastrous box office returns of his first major studio picture. Up until this point, he was still a genuine independent since Halloween wasn’t a major hit upon release and The Fog was a small, 1.1-million-dollar ghost story. Escape from New York was a gritty Avco-Embassy production. People were repulsed by Bottin’s unbelievably shocking effects and yet one has to wonder what might’ve happened if The Thing had been released in October or perhaps even in the dump months of January and February. Instead, it had to contend with Spielberg’s E.T., a box-office juggernaut featuring an equally creepy, yet somehow loveable being from another world. Even scenes that don’t feature actual monster madness are nasty, with Blair’s autopsy scenes and the discovery of half-finished Thing replicants being stand-outs. The discovery of the decimated Norwegian research center, complete with frozen strands of blood sticking out of a man’s wrists and the stretched out, agonized expression of a man burnt to a crisp, mid-transformation, are evocative and icky. By the way though, wouldn’t transporting all those bodies back in the chopper make it stink to high heaven?

Carpenter had been the master of “imagination” horror films: very little blood and leaving the more extreme violence to the viewer’s imagination. In an interview, Carpenter explained: “People were appalled. If you’re making a horror movie, you’re not supposed to show the devil. Well, if you have a really great devil, why wouldn’t you show that?” It’s a solid argument that I tend to agree with. I adore gory films, but if the gore doesn’t serve any kind of narrative purpose, it just doesn’t work. Here, they were doing something that had never been done before, so no wonder people were taken aback. And yet, it’s justified because we’re still left scratching our heads going, “How the hell did they do that?” Yes, he went out on quite the limb and even fell off the precipice, but through constant re-evaluation and a loyal, rabid fanbase, The Thing is a flat-out masterwork. As MacReady says: “Trust is a tough thing to come by these days,” and I trust Carpenter knows that people have finally come around. And anybody who doesn’t think so should “Back off. Way off.”