The Stepfather (1987)

- nickkarner

- Nov 4, 2021

- 12 min read

There’s a running joke which has permeated throughout Justin Roiland and Dan Harmon’s hilarious animated show Rick and Morty. The father of the somewhat dim, always horny Morty is the plainly named Jerry Smith. A man who is both simple and complex, Jerry proves time and time again to have very poor judgement and often prompts characters to utter the immortal phrase: “Fuckin’ Jerry.” This bit of dialogue now tends to be applied to anyone or anything that goes wrong due to a stupid mistake. On Robot Chicken, another excellent Adult Swim program, there’s a tiny sketch in which another member of E.T.’s race flies past the moon alongside Elliott on his bike. However, this E.T., who happens to be named Jerry, is in a sweet convertible and sports sunglasses. The titular E.T. shakes his head and mutters, “Fuckin’ Jerry. He’s always straight-up killing it.” Although he only means that said Jerry is a super cool alien dude, a more literal interpretation could be applied to the “Jerry” of 1987’s family horror-thriller The Stepfather. There’s just something appropriate about naming a character of true evil Jerry.

The Stepfather began as an idea by book editor Carolyn Lefcourt. Actually, that’s not entirely accurate, since the inspiration came from the infamous and, at the time, unsolved murder of the List family, which took place in 1971, by patriarch John List. The nature with which List went about killing the family was particularly noteworthy due to its meticulous nature. List sent various letters to his children’s schools and one to his minister as well as implying to his neighbors that the family was going on a long trip. All photographs of him were destroyed and nearly a month passed before the bodies were discovered. List had disappeared without a trace and both investigators and speculators came to believe the man had either killed himself or left the country. Instead, he’d relocate from New Jersey to Colorado, where he’d meet and marry a woman, essentially erasing his previous life and starting over.

Lefcourt presented this idea to writer Brian Garfield, whose most famous work remains his oft-adapted novel Death Wish. He’d later use a couple of elements from List’s story in his comedic adventure novel Hopscotch, where a former CIA agent would skip the whole murder thing but assume a new identity nonetheless. Due to his belief that he wasn’t the correct author to pen a novel based on a grisly murder in the vein of Robert Bloch’s work on the Ed Gein-inspired Psycho, he brought the story to the attention of highly-accomplished and critically-acclaimed crime novelist Donald E. Westlake with the idea of turning it into a screenplay. Unlike Bloch’s novel, the entirety of List’s story hadn’t been uncovered yet due to the murderer’s disappearance. This meant that Westlake would have to essentially “fill in the blanks” based off of the limited information at hand. At one point, there was speculation that John List was really the mysterious robber and hijacker D.B. Cooper due to the timing of his and Cooper’s crime.

Westlake found alarming and oddly personal connections to John List. Growing up in the Depression, his father would leave every day for “work,” but he’d actually lost his job weeks prior and would spend his days in a desperate search for employment. Every Friday, he’d go to the family’s bank and take money out of their own account, pretending it was his “salary.” His ruse was discovered sometime later. Another element was the crime taking place in Union County, New Jersey, an area quite close to where Westlake had lived with his family for a number of years. While Garfield and Lefcourt received story credit, the final script would be credited solely to Westlake, with an uncredited rewrite having been done by Dreamscape and (ugh) Star Trek V scribe David Loughery.

Westlake’s work has been adapted for the screen a number of times, most notably his novel “The Hunter,” which became the basis for John Boorman’s excellent Point Blank, while his novel “The Hot Rock” led to a highly enjoyable 1972 caper comedy. He’d even written a similarly-themed story, “Pity Him Afterwards,” which revolved around an escaped mental patient who steals the identity of a man he’s murdered, then sets to work murdering others. A variation on this idea would end up in the artistically-inferior Stepfather sequel. In a move which practically translates into “the adding of chocolate to milk,” Westlake would receive an Oscar nomination for his adaptation of fellow crime novel writer Jim Thompson’s The Grifters. The Stepfather screenplay was completed in the mid-70's but didn’t get picked up until ITC Entertainment’s Jay Benson, being a fan of Westlake’s novels, decided to produce it in the mid-80's. Westlake achieved a rare feat for a screenwriter: total control over the story. This was after all, a hypothetical take on the List story, so this was very much a work of fiction laced with real-life inspirations. Director Joseph Ruben, coming off the mildly-successful Dreamscape, was hired and suggested an ultimately critical script change: the elimination of List stand-in Jerry Blake’s backstory.

When Ruben initially read the script, he found that despite the main character’s psychotic, delusional nature, his wants and needs were very much something most civilized people want. “The beautiful home, the beautiful wife, the beautiful Norman Rockwell family.” By beginning the film with Jerry undergoing a complete transformation after the slaughter of his latest family, the viewer is dropped right into the murderer’s orbit and there’s no need to delve deeper into the character’s psychology, particularly when said character is played by the then-relatively unknown and absolutely electric Terry O’Quinn.

Both Westlake and Ruben were quite frankly delighted by their good luck in discovering O’Quinn. Westlake had previously expressed his displeasure with the way some actors had embodied his characters but he was taken aback at how “stunningly perfect O’Quinn was in the role.” Ditto Ruben, who recalled while shooting one of Jerry’s astonishing freak-outs in his basement thinking: “Holy shit. This is an amazing moment that I'm watching for this actor.” While the production had attempted to go after much bigger fish, they’d been turned down flat multiple times due to the unrepentant darkness of the character. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise since Terry O’Quinn, in his first-ever lead role, is a revelation.

O’Quinn’s previous work hadn’t given any indication of the emotional depths he could achieve in The Stepfather, but his resume both before and after the film includes highly memorable, and in some cases infamous work. Heaven’s Gate, SpaceCamp, Silver Bullet, Pin, Blind Fury, Tombstone, and the role with which he’ll forever be associated with, the tragic fan favorite John Locke on the divisive TV series Lost. The control with which he approaches Jerry Blake, a man whose unrealistic image of a perfect family continuously leads to terror and bloodshed, is pitch perfect. His habit of giving heartfelt speeches which he can barely finish due to his emotions overtaking him underline how vigorously he trusts in his own personal beliefs and dreams. At one point, a character mentions how Jerry must’ve watched too many episodes of The Waltons. I’ve personally never seen The Waltons, but the “perfect family” association with that show has entered the pop culture lexicon and I immediately understand exactly what the film is alluding to.

The real List was a deeply devout Lutheran and wholeheartedly believed in the word of God. Although this is only hinted at, particularly in a dinner scene where he can barely finish his own prayer due to his emotions taking over, it’s clear religion plays a big role in his conception of a perfect family unit. O’Quinn’s ability to shift from uncontrollable rage to loving father figure in the blink of an eye could’ve been comically ridiculous, but he finds the humanity in a loathsome character and makes his every move and action believable, plausible, and even understandable. His backstory is hinted at in snatches of dialogue, and dare I say it, one even comes to slightly sympathize with him, despite his calculated deception and selfishly nihilistic actions. During the writing process, Westlake asked himself the simple question: “If I had done what John List did, what would I do next?” The answer he came up with was simple and troubling: “I’d pick up right where I left off.”

The opening of the film perfectly encapsulates the dark underbelly of suburbia which David Lynch had explored a year prior in Blue Velvet with a crane shot overlooking a perfect neighborhood. Gliding over to just one of the many cookie-cutter residences on this seemingly boring little street, the camera tracks into a window. O’Quinn, looking like a scruffy lumberjack and covered in blood, scrupulously scrubs himself clean and, using a razor and a pair of scissors, transforms from a mountain man-type into someone resembling a stuffy college professor. The former ‘Henry Morrison’ is now mild-mannered real estate agent, Jerry Blake. In an uncompromisingly grim single take, shot by frequent Ruben cinematographer John Lindley (Pleasantville, The Serpent and the Rainbow), Jerry passes a single bloody handprint on the wall before stopping to adjust a pillow which has fallen off a chair. He’s absolutely indifferent to the absolute massacre in his living room, where dead bodies lie strewn about and the walls have been painted with blood. He whistles “Camptown Races” as he steps over the corpse of a little girl, whose gore-encrusted teddy bear lies nearby. He dumps the suitcase over the side of a ferry and he’s off to begin his new life. I was reminded of the words Gan imparted to Roland Deschain at the conclusion of Stephen King’s “The Dark Tower”: “Perhaps this time the result will be different.”

A year passes and Jerry’s established himself at American Eagle Realty, which I assume was before they restructured and became a clothing company, and he’s got an attractive new wife and a willful teenage stepdaughter. Widowed mother Susan (Shelley Hack, The King of Comedy) and daughter Stephanie (Jill Schoelen, Popcorn) have a lovely relationship, exemplified by their epic leaf battle, but while Susan absolutely adores her new husband, Stephanie neither trusts nor particularly likes Jerry, despite his pleasant demeanor and gift of an adorable puppy. The film slightly resembles a reverse of Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, but in this case, the beloved uncle elicits skepticism instead of devotion. Rather than lash out at Jerry due to her mother’s infatuation, Stephanie instead acts out at school, resulting in her expulsion. Jerry can’t stand the idea of his stepdaughter leaving for boarding school, “It’s not a family without children,” so he convinces the school to take her back.

As Stephanie’s suspicions about her new stepfather grow, the brother of one of Jerry’s previous victims doggedly pursues any leads he can find. Jim Ogilvie (Stephen Shellen, The Bodyguard) suspects that his sister’s killer is still at large within a specific radius and has set up a whole new life for himself. While Ogilvie’s story sets up an interesting parallel story to Stephanie’s investigation, it ultimately doesn’t lead to much as Jim becomes yet another victim of Jerry’s wrath. After Jim is slain near the film’s conclusion, Jerry offers a helpful word of advice: “Next time Jim, call before you stop by.”

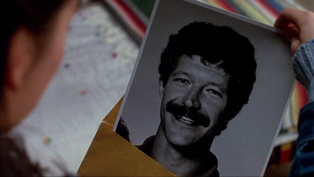

Stephanie believes that Jerry may be the very man Jim is searching for, so she requests a photo of ‘Henry Morrison’ from the Seattle Examiner. Unfortunately, Jerry, cool as a cucumber and clever as always, happens to intercept the photo, which looks like a professional headshot. Did Henry do some local theatre? Perhaps he played Captain Hook at the local high school? Nah, that part’s way too mean for good ol’ Henry. Jerry replaces the photo with what appears to be a pic of Olympic Gold medalist Mark Spitz.

Anyways, the article about the killings is passed around by friends and neighbors at a picnic Jerry hosts. It’s significant not just because he breaks down during his corny speech about family, but for his absolutely awful sweater. Seriously. 80’s sweaters, man. Jerry reads the article and lays it on real thick, but convincingly emotes his shock that someone could do this to the people he loved. “Maybe they disappointed him,” he ominously suggests.

Later in the basement, while Stephanie snags two giant tubs of ice cream, Jerry comes storming down, ranting and raving to himself in a scene of stunning intensity. When he notices Stephanie, he shrugs it off with relative ease, blaming his outburst on his need to “let off some steam.”

Stephanie’s been seeing a therapist, Dr. Bondurant (Charles Lanyer, Die Hard 2), who devises a plan to get some information out of the seemingly therapy-averse Jerry by posing as a potential home buyer. While the film contains relatively little violence until its explosive conclusion, the violence it does display is disturbingly realistic. After Bondurant accidentally gives himself away during their conversation, Jerry grabs a two-by-four and begins beating him unmerciful. In most films, a single whop with a piece of wood is enough to fell a victim, but the human body is more resilient. Jerry has to hit the good doctor multiple times to kill him and it’s quite brutal. With a creative streak that borders on supervillainy, Jerry fakes a massive car explosion and the doctor’s death is ruled an accident.

In Jerry’s mind, the perfect family means no outsiders and that also means his offspring (whether natural or inherited) must practice a chaste lifestyle. Even when Susan jokingly refers to all of the boys Stephanie will be fending off, Jerry’s obvious discomfort shows through. Stephanie locks lips with a nice classmate outside her front door and hoo boy, Jerry is beyond pissed. His apoplectic response to a tiny peck is frightening. “He was trying to rape our daughter!” he screams. When he yells that Stephanie is only 16, the boy humorously retorts “So am I!” Susan takes Jerry’s side and even slaps Stephanie, but then she turns her anger on Jerry for his overreaction, which in turn sends him on track to rinse and repeat his life.

He takes the ferry to another town, transforming into Bill Hodgkins, a glasses-wearing, slightly balding insurance salesman, a profession List himself tried and failed at. He even begins laying the groundwork by introducing himself to a single mother living next door to him. The level of detail the film pays to Blake’s preparation and O’Quinn’s charming manner make all of these events hauntingly believable. When Jim surveys the previous house Jerry lived in, the similarities between his old and new basement workshop, along with a family polaroid, definitely indicate a serial killer’s pattern.

It’s a clever choice that Stephanie actually doesn’t discover Jerry’s true identity until she’s literally confronted with a bloody knife wielded by her stepfather. She’s a bit too busy indulging in an obligatory 80’s horror movie trope: a shower featuring random, pointless nudity. In the film’s climactic and most shocking scene, Susan confronts Jerry about quitting his job and as Ruben puts it, “the circuits don’t quite fire right.” He mixes up his various identities and has to stop, uttering the famous line: “Wait a minute...who am I here?” He turns to Susan, smiling warmly, then smashes her across the face with the phone. It’s a visceral moment which takes your breath away. He continues the beating by punching her in the face, sending her tumbling down the basement stairs. Before he can finish her off, Jim arrives, but he’s stabbed quite quickly, although not before Jerry recognizes him and even cheerfully greets him.

Stephanie’s able to fend Jerry off after he smashes through her bathroom door, but he very nearly delivers the final blow before Susan manages to shoot Jerry with Jim’s gun. Just as Jerry is about to fall backward after being shot three times, he whispers “I love you” to Stephanie before tumbling down the stairs. An elaborate bird house Jerry had built earlier is torn down with an adorable little electric saw. You almost expect a little mini-Jerry to come crawling out of the demolished house, hellbent on exacting his teeny, tiny revenge.

While O’Quinn absolutely dominates the film, Schoelen gives a fine supporting performance. Hack’s work is sympathetic, but occasionally her delivery reads as phony and flat. The technical aspects of the film are fine, but the score is another matter altogether. The 80’s were not a good time for film scores due to the proliferation of the synthesizer. It was a cost-effective measure, which is forgivable, and work by Goblin and Tangerine Dream, among others, was quite good. Patrick Moraz’s score, on the other hand, nearly torpedoes the entire film. It’s that bad. Due to the bleak nature of the material, I don’t believe this music is supposed to be intentionally parodic, but certain scenes, particularly a bike riding scene, is laughably cheesy at best and horribly inappropriate at worst. The music following Jerry’s outburst on the porch sounds as if he’s about to burst into song. Very ineffective and it disastrously dates an otherwise fairly timeless tale.

Two years after the release of The Stepfather and only 5 months before the release of Stepfather 2: Make Room for Daddy, John List would be caught on June 1, 1989 thanks to a broadcast of America’s Most Wanted which covered the 18-year-old crime. The true story was finally told and it fit pretty neatly among other crimes of a similar nature. List was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and based on his extreme religious views within an increasingly desperate situation, he came to the conclusion that rather than go on welfare, it would be an act of mercy to simply murder every member of his family and send them to “heaven.” Since suicide is a mortal sin, he would have to live with his actions, which I certainly hope tormented him. I don’t believe it did very much, however, based on one key difference between reality and the film.

In the film, Jerry coaxes Stephanie’s terrier mix puppy over to him with the intent to kill it, but fortunately, he’s distracted and the dog gets away. In reality, List killed their beloved pet Tinkerbelle. Why? Did Tinkerbelle also need to be sent to “heaven” lest she fall sway to the temptations brought about during desperate times? Why not just let her go? An argument could be made that either she’d starve to death anyways or perhaps a neighbor would find her and bring her back, resulting in the corpses being found sooner. That may be, but it proves a point that despite List’s insistence that these were mercy killings, his painstaking efforts to get away scot-free and eventual resettlement make him a hypocrite of the highest order. At least we got a fine film out of this tragedy. Thanks a bunch, John, you miserable sack of shit.

Comments