Spirited Away (2001)

- nickkarner

- Jun 2, 2022

- 12 min read

“This is all leading to something. I can feel it!”

A journey. Arguably one of the simplest yet most versatile plot devices in all of media is the simple act of moving from one place to another. A film can take you on a journey. Ditto a book, a song, a video game, the list goes on and on. The journey, whether literal or emotional, provides the mix of fear and excitement which comes with exploring unknown worlds. It’s beguiling. For master animation writer/director Hayao Miyazaki, I feel that the journeys many of his central characters take parallel his own path as a filmmaker. From Cagliostro and Nausicaa all the way to Princess Mononoke, he honed and excelled at his craft. One could even make the argument that Mononoke was the culmination of his career, and I would be happy to agree. For me, however, I believe everything was leading up to the monumental achievement of his 2001 feature, Spirited Away. Not only was it an artistic achievement of the highest order, but it was also a financial success, proving that it was possible to merge art and commerce. Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi, as it’s known in Japan, represents a filmmaker working at the height of his powers. That’s not to say the subsequent work hasn’t been excellent. Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponyo, and The Wind Rises are all good-to-great films. He may be human, but I don’t think Miyazaki is capable of making a “bad” film. Some are just better than others.

My daughter was once laid out with a seriously bad case of the flu. We’re talking, “can’t keep anything down, but she’s thirsty all the time” bad. Limp as a rag, there was nothing to be done but sit around and watch movies. Usually, her attention span isn’t up to snuff for a full movie and she’ll wander over to her Lego collection or maybe mess with her dolls. This time, she was a captive audience, mainly because it wasn’t fun to move around. The longer the films, the quicker the day went by, so the 2-hour runtime of Spirited Away was very alluring. I was a bit nervous since it’s not exactly your standard Disney fare, but my fears were alleviated by her absolute joy in seeing a young girl persevere despite near-impossible odds.

The gentle, elegant piano theme by Miyazaki’s favorite composer, Joe Hisaishi, belies the intensity of a film that features a few frightening scenes of genuine ferocity. For now, the score feels like a feather floating in the wind as the Ogino family; Akio, Yuko, and young Chihiro drive to their new home in a new town. Chihiro glumly clings to a bouquet of flowers, complaining that the one time she gets flowers, it’s a farewell bouquet. Coming to the end of a paved road, they see a path leading through the woods, which her dad decides to take since he has “four-wheel drive.” Yeah, that’ll keep ‘em safe. He drives through the forest like a maniac, until they’re stopped by a high wall with a tunnel entrance. Chihiro immediately senses danger and turns out to be the smart one in the family. Her dad insists on exploring, possibly goaded on by the wind literally pulling them in, and they discover an abandoned theme park, a popular attraction in the 90’s. They smell something delicious and discover that although no one is around, piles of piping hot food, which do look great, are just sitting in a stall. Chihiro abstains, but her parents chow down. She wanders off, coming upon a large building with a smoking chimney, despite the absence of people. Suddenly, a young man, Haku, forcefully tells her to leave immediately. She’s a little weirded out, even wondering aloud, “What’s up with him?”

She rushes back to her parents, who have grown in size as they gorge themselves. Her dad turns and she discovers to her horror that he, and her mother, have been transformed into pigs. It’s a chilling and upsetting scene, with the animation on the pigs being slightly grotesque and not helped by an unseen figure whipping them away from the food. The sun begins to set as she runs through the theme park, completely freaked out and unsure of what to do. The lights begin to glow and strange, shadowy spirits emerge and float all around her. A huge river that was dry only an hour ago is now impassable, with a river boat fast approaching. Various creature and ghostlike apparitions exit the boat. She huddles on the shore, believing it’s all a dream and desperate to wake up. Haku reappears as her body begins to literally fade. He tells her to eat something from his world or else she’ll disappear. He appears to have powers and is willing to help her. He leads her through various alleys, including a huge pig pen, and tells her she must hold her breath while crossing the bridge. This will help her avoid detection while they enter the building she saw earlier, which turns out to be a bathhouse for spirits to come and replenish themselves. I didn’t realize spirits needed a spa day, but it’s certainly an original idea.

The creatures here are varied and highly creative. The humanoid men resemble frogs while the women, though relatively normal, tower above the men. There are also literal frogs roaming around, one of which startles her. She breathes, but Haku is able to whisk her away before she’s spotted, blowing through the legs of some of the female staff. He transfers his knowledge by touching her forehead, advising her to find Kamaji, the boiler man, then ask for a job from Yubaba, the witch who owns the bathhouse. She asks how he knows her name, and he enigmatically says he’s “known her since she was very young.”

She makes her way down some very steep stairs slowly, but loses her balance and has to run down at top speed lest she fall. It’s an amusingly realistic moment since the instinct for most of us when traversing stairs is to increase speed if we have no rail and feel gravity tightening its grip. She encounters Kamaji, who has multiple arms that stretch out for days as he gathers various herbs to send through the water system. To keep the boiler running, he’s cast a spell on black soot, which take the form of soot sprites that were first seen in Miyazaki’s glorious My Neighbor Totoro (1988). They’re a sight to behold, wordlessly carrying large pieces of coal to the furnace. Although he seems cantankerous and has no interest in the follies of humans, something about Chihiro’s insistence and her willingness to help the soot spirits touches him. One of the workers, Lin, enters with some food for Kamaji and star candy for the sprites. She gasps, “A human!” when she sees Chihiro, but Kamaji calmly tells her she’s his granddaughter and that she wants to see Yubaba for a job. He offers Lin a roasted newt as payment for the favor, which must be a rare delicacy, indeed.

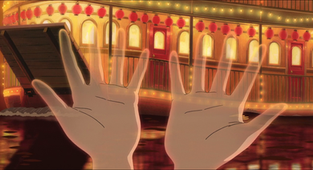

The hustle and bustle of the bathhouse is in full swing as Lin and Chihiro make their way to the elevator. A large and silent beast, known as the Radish Spirit, rides up the elevator with Chihiro in an amusing and wordless scene. Chihiro comes upon a very rude door knocker, then gets yanked by invisible forces controlled by Yubaba through a huge and labyrinthine hallway. She’s quite the creation. A squat woman with an enormous head and decked out in jewels, she’s haggard but also extremely capable and strong. Weird creatures, including a bird with a Yubaba-like face and a set of three bouncing heads carry on nearby. She threatens to transform Chihiro just to run her off and Chihiro is visibly shaking as she asks for a job. Yubaba literally zips her mouth shut. She then tries to intimidate Chihiro by rushing right at her. Chihiro can barely maintain her composure, but she shows incredible courage and insists on working for Yubaba. It turns out the witch took an oath to accept anyone who requested a job, so really, she doesn’t have a choice, although fortunately, Yubaba’s very large infant is having a tantrum, so she wants to get this over with. Yubaba casually commands her to “Sign your name away,” which is secretly her way of controlling anyone who works for her. Chihiro’s writing floats off the contract and into Yubaba’s outstretched palm. Now, she will no longer be Chihiro. She’ll be Sen.

Lin shows her to their sleeping quarters and gives her some clothes. The whirlwind events of the last few hours finally catch up with Chihiro/Sen and she bawls her eyes out. It’s deeply sad and understandable. She’s a child being forced into a situation beyond her control. She struggles to sleep and then receives a message to meet Haku at the pig pen. She’s already begun to forget her name, but she finds the card from her bouquet in her pocket. Haku tells her to keep the card safe so Yubaba can’t control her. He transforms into a dragon and flies off.

The work is hard for Chihiro and she can barely keep up. A strange and mute spirit with a black form and a painted face mask stands outside the bathhouse windows. Chihiro is kind to him and leaves the window open for him to enter. She needs a bath token to clean the big tub, which the foreman won’t give her. In fact, she adorably asks Lin what a foreman is. No Face vanishes and steals a token for her. Just as they’re scrubbing the sludge off the tub’s interior, a giant stink spirit appears at the entrance in desperate need of a bath. The staff informs Yubaba through a pretty funny skull phone. She forces Chihiro to take care of the “customer,” who drops slime-covered money into her hands. In a great scene, she struggles through the mass of pollution, this thing is practically Hedorah from Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster (1971), and notices something stuck in the spirit’s side. Removing it with help from the bathhouse staff, a massive amount of garbage flows out, revealing the stink spirit to be a River Spirit, who gives her a strange edible ball.

No Face is still wandering the halls and when a mouthy frog encounters him, he lures the amphibian closer with a handful of gold. Suddenly, he shoves the frog in his mouth, which gives him the power of speech. More of the staff arrive and No Face produces piles of gold, causing an uproar from the likely under-paid staff, who jockey to gain the favor of this new wealthy guest.

As Chihiro watches a train travel over the water in the sea, she sees Haku, in dragon form, being attacked by hundreds of bird-like creatures made of paper. In a particularly bloody scene, she gets him into a secluded area, where he appears more animal than man, lashing out and growling. A single paper bird attaches itself to Chihiro’s back before Haku flies to another part of the bathhouse. Chihiro rushes off to help him. No Face stops her and tries to give her the largest amount of gold any of the staff have ever seen, but she politely refuses, which enrages No Face. He begins eating the workers and screaming for her to return.

She overhears Yubaba planning to let Haku die, even though his mission was to steal a magical golden seal from Yubaba’s twin sister, Zeniba. Before Chihiro can get over to Haku, the big baby Boh grabs her and demands she play with him. She tries to get away but he’s incredibly strong. Fortunately, he’s also got a Howard Hughes thing going on and believes germs will kill him, so she shows him her bloody hand and he lets go. The paper bird reveals itself to be a form of Zeniba, a literal copy of Yubaba in every way except for her fondness for Boh. She transforms him into a mouse and the weird-faced harpy bird into a tiny insect-like bird. The three severed heads are changed into the big baby, who now has a massive appetite. Chihiro and Haku fall through a pit and she briefly remembers being pulled through a river. They crash into the boiler room, where Haku continues to die. She forces a piece of the gift from the river spirit into his mouth and holds his head tight. It’s heartbreaking as she desperately wants to help her friend but he’s so distraught that he turns violent. His appearance slightly resembles a dog, drudging up memories for anyone who has had a sick pet who needs to take medicine. Trust me, it can be very difficult and frustrating to make a dog swallow pills. A filthy slug spews out of Haku and Chihiro squishes it. He collapses. Kamaji advises her to find Zeniba in Swamp Bottom and gives her a 40-year-old, yellowing set of train tickets, something that’s apparently extremely hard to come by.

Yubaba summons Chihiro and she confronts No Face, who has grown huge from consuming so many people and dishes of food. She bravely steps forward, looking tiny compared to his towering form. He desperately wants to please her, but she tells him to leave, confusing and angering him further. She tosses the rest of the river spirit’s ball into his mouth, causing him to throw up the people he ate, who are luckily alive, as well as the rest of his meal. He chases her through the hallways in the scariest scene of the film. He returns to his old form and Chihiro sees that he’s just a lonely spirit. She invites him, along with the mouse and bird, to come along.

In one of the quietest and most hauntingly beautiful sequences, she boards the train, which is filled with spirits that are dressed like it’s the 1940’s. The score is melancholy and emphasizes her loneliness. It’s one of the most adult scenes since it slows down the action, allowing Chihiro and the audience to take stock of her situation. It’s difficult to describe why this scene feels so powerful. Perhaps it’s the faceless spirit girl standing alone at a station or maybe Chihiro silently realizing that her parents could be eaten at any moment. The idea of a small girl alone in such a bizarre and even dangerous world has never been done in quite this way. Perhaps the only legitimate comparison is Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

They arrive in Swamp Bottom, where a Pixar-inspired bouncing light guides their way. They enter Zeniba’s modest home and she returns the gold seal to her. Zeniba turns out to be a sweet and kind old lady, who requests that Chihiro call her Granny. Definitely another Totoro reference. With help from Chihiro’s friends, she weaves her a sparkling purple hairband for protection. Haku returns and tells Chihiro that as long as Boh is returned, she’ll only have to face one more test from Yubaba, then she and her parents will be free. No Face stays with Zeniba and she flies off with Haku, who has turned back into a dragon.

Probably the most magical scene comes next, when Chihiro whispers to Haku that she keeps remembering a moment from her childhood where she nearly drowned after falling into a river. She somehow found herself safely brought back to shore. She believes that Haku’s name, which he can’t remember, is the Kohaku River. His skin suddenly crystallizes and he changes back to himself again. “You did it, Chihiro!” cries Haku. The river had been drained to build an apartment complex, explaining why Haku could never find his way home. Her eyes well up with tears, which flow upward since they’re falling out of the sky. It’s a breathtaking scene and very moving.

Yubaba, despite the protestations of everyone, including Boh, forces Chihiro to choose which pigs are her parents. Chihiro correctly realizes none of them are her parents, forcing Yubaba to free her. Haku walks her back to the steps of the park, which is once again dilapidated. He tells her she’ll find her parents at the end of the tunnel and to not look back. The mention of not looking back seems to allude to a transition as well as a need to not dwell on the past. Her folks are waiting for her, lightly chastising Chihiro for running off. They clearly don’t remember anything. For a moment, it almost appears that all of this has somehow been a dream, but Miyazaki is cleverer than that. As in Totoro, it doesn’t matter whether the fantastical occurrences are real, it’s the journey the heroine has taken. It’s left wonderfully ambiguous because the car is covered in leaves and the interior is dusty, making it clear a great deal of time has passed despite her parents believing they’ve only been gone for less than an hour. We also notice the purple band is still in Chihiro’s hair. As they drive off, Chihiro mentions that she thinks she can handle a new school. I would think so.

John Lasseter, the disgraced Pixar co-founder, has always said Hayao Miyazaki was a major influence. He credits Miyazaki’s style and storytelling abilities as the reason he found such huge success in the animation world. Beginning with Spirited Away and displeased with the original English dubs of Miyazaki’s previous work, he managed to attract impressive voice casts to re-dub the films into English, making certain the dialogue matched the original animation’s lip movement. I’ll always choose subtitles over dubbing, but watching this with my daughter, it’s a highly enjoyable experience because the dialogue feels natural and not awkwardly translated. Daveigh Chase, who would lend her voice to Lilo, terrify audiences in the American version of The Ring (2002), and play Donnie Darko’s younger sister, imbues Chihiro with the right amount of spunk and vulnerability. She makes you want to reach through the screen to save her. The cast is rounded out by fine work for Haku (the always charming James Marsden), Yubaba/Zeniba (a glowering and uncompromising Suzanne Pleshette), Kamaji (David Ogden ‘Cogsworth!” Stiers), Tara Strong as Boh, Lauren Holly and Michael Chiklis as her parents, and best of all, Susan Egan as Lin, whose distinctive voice and tough yet caring performance is a highlight of the film. Of course, you know within two seconds that it’s Meg from Hercules (1987), but that’s part of the fun.

Spirited Away hit me at just the right time in my own filmgoing journey. I had just graduated high school the previous Spring and had grown up on a steady diet of Disney, Pixar, Don Bluth, and an odd assortment of animated TV specials. I’d never seen anything like it. The film presents a heroine who appears terrified by her newfound responsibilities and must search within herself for the strength and courage to do what must be done. With my own life stretched out before me, I identified with Chihiro and understood the colossal and likely difficult road ahead. It was nice to know I wasn’t alone.

Comments